When writing your research paper, you will (assuming a holistic approach to the process) find yourself making assertions about the state of the existing research. In order to both strengthen the validity of these claims and avoid any potentially-damaging accusations of plagiarism, it is vital that all outside sources are cited properly. Consistency across your referencing is key in academic writing. This article will delve into citing within text in Chicago style.

Definition: Chicago in-text citation

Chicago in-text citations are used whenever you refer to an external source, to help your readers understand the context.

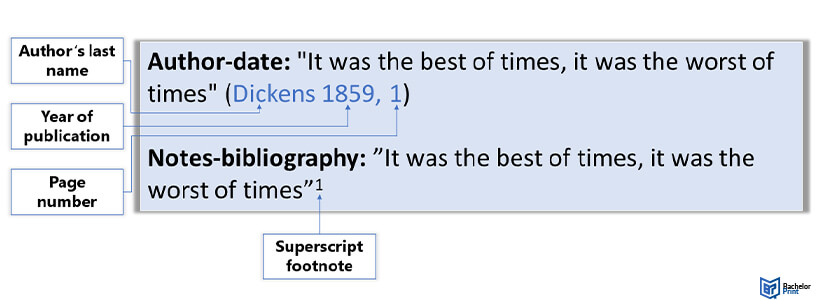

There exist two options for Chicago in-text citation: the author-date style and the notes-bibliography style.

The former approach appends the author’s name, year of publication, and relevant page number(s) in parentheses, whilst the latter uses superscript numbers only adding more detail in the form of footnotes or endnotes:

Chicago in-text citation: Which style?

The two approaches to formatting a Chicago in-text citation are not worlds apart in terms of stylistic rules, nevertheless, it is important to understand the differences.

| Chicago in-text citation in author-date style | Chicago in-text citation in notes-bibliography style |

| • Includes minimal in-text reference to publication details. • The information is enclosed in parentheses |

• Includes more information, e.g., individual pages • Footnotes are collated together into a unified bibliography at the end |

The Chicago in-text citation in notes-bibliography style is most commonly favored by subjects in the humanities, whilst scientific disciplines tend to lean towards the author-date method. Whichever route you opt to go for your Chicago in-text citation, it is vital to be as thorough as possible when referencing.

Chicago in-text citation: Author-date

This style is a parenthetical citation including the author’s name alongside the year of publication. You would also typically include the page number (or a page range) where your quoted material can be found:

There is little variation in formatting a Chicago in-text citation based on the type of source, though an explicit distinction should be drawn when referencing an entire chapter rather than a single page.

Although these details may seem scant on their own, when combined with the more maximal coverage of the appended reference list, they form a complete picture of source attribution for your paper that your readers can peruse at their convenience.

Note: If you have introduced the author’s name in the text, then it should be omitted from any parentheses relating to that reference when following Chicago in-text citation style.

Placement of the citations in the text

Although there are plenty of fairly stringent guidelines around Chicago in-text citation, the author-date style does afford a manner of compositional freedom depending on which part of the reference you are looking to emphasize. Hence, we can identify two distinct approaches of Chicago in-text citations:

- Author-prominent

- Information-prominent

If you’re not making a direct quotation, you may find that the assertions you are making are aggregated from multiple sources of existing research. In these cases, you should list all sources in a single set of parentheses, separated by a semicolon, as below:

Chicago in-text citation: Footnotes or endnotes

Chicago in-text citation to outside sources is limited to superscript text indicative of a footnote or endnote. These additional notes will then contain full bibliographic information for each source as shown in the following format:

Chicago in-text citation: Full notes and short notes

Chicago in-text citation may be divided into two formats: Full notes and short notes. These should be viewed as notes which provide all of the information about the source vs. notes which provide only some of it:

The first Chicago in-text citation reference is made to a specific source and should be cited in full. To reduce the amount of space taken up by footnotes, subsequent allusions may use the shortened form. The use of “ibid.” is now discouraged, but there is no hard rule against it; i.e., one should revert to institutional preference in times of uncertainty.

Moreover, there may be slight variations in formatting depending on the type of source. The below demonstrates full and short note citation formatting for the same four sources: A website, a book, a chapter in a volume, and a journal article. Here, much of the information is omitted when the note is shortened.

Chicago in-text citation: Footnotes or endnotes?

The only real distinction between Chicago in-text citation footnotes and endnotes is their position within the manuscript; content-wise, they are functionally synonymous:

- Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page

- Endnotes appear on the final page following your conclusion.

When grouping all of your Chicago in-text citations under an endnote section, keep in mind that it may be considerably more difficult for readers to check your sources.

When there are multiple authors, a Chicago in-text citation is best to navigate through the use of “et al.”, using four authors as the barometer:

Chicago in-text citation: Missing information

As we have reiterated throughout this article, it is important to be comprehensive when referencing Chicago in-text citation, but this is not always possible. Occasionally, you may find sources for which full bibliographic information is unavailable. The three subsections below offer more information.

No page number

Page numbers should always be included when available, however, they’re not always available. In these scenarios, don’t editorialize and try to break it down into your own numbered sections. Instead, omit this information from the reference:

No publication date

Missing a publication date occurs very often: Here, the date from the Chicago in-text citation must be omitted and replaced with ‘n.d.’ in the Chicago in-text citation as well as the reference list. For online sources, you can provide additional context through the inclusion of a “Date Accessed”:

No author

For sources with no identifiable author, you may try and find an institution or organization that can be used instead. Failing that, you should use a short Chicago in-text citation of the title. It is essential that you never attribute a source to “Anonymous”, unless the cited text itself makes reference to an anonymous author.

FAQs

“Et al.” has historically been used when referring to a source with four or more authors. Though the bibliography entry would list all authors (except when the number is greater than ten), the Chicago in-text citation would refer to the first author only, substituting “et al.” for the rest.

Generally, no: Completeness is key when it comes to referencing. One exception is personal communications. These should still be identified as such in-text, but are typically left out of any bibliographies.

This Latin borrowing frequently appears in academic writing. It indicates when consecutive references are taken from a common source, though its use is now discouraged in favor of shortened citations.

Page number-level citation is not required, for example, if you are making reference more broadly to the specific ideas presented by a source.