Thematic analysis is a methodolgy that helps scientific researchers understand unquantifiable, complex data with open-ended questions and transcripts. Applied analysis carefully examines qualitative prose statements (i.e. subject interviews, transcripts, documents) via a detailed, systematic 6-step schema. Recurring patterns are then identified, grouped, and picked apart for deeper insights.

Definition: Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is fantastic for empirical humanitarian and scientific experimenters who want to explore highly subjective topics of interest. You might use thematic analysis to study ‘intangibles’ such as people’s experiences, perceptions, and nuanced opinions.

How does it work? By asking respondent(s) the same open-ended questions, common and unique themes reveal themselves. Qualitative conclusions can be formed without statistical tests for correlation and causation.

The analytical schema was first published as a 2006 paper by psychologists Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. They developed a straightforward, 6-step experimental method to simplify qualitative data analysis and add repeatability to test cycles.

When is it relevant to use thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is ideal when your experimental research needs deeper insight into what a sampled group of people think. It’s a versatile, adaptable methodology that often opens up new areas of exploration.

Why? While it’s possible to poll public opinion quantitatively with formulaic questions (e.g. Do you approve/disapprove?), this may risk narrowing responses and leading participants. Cold statistics might also miss the depth behind controversial and subjective topics such as politics and religion.

Thematic analysis keeps more of an open mind as to what may get back from testing. By adopting a focus group, interview-led approach, observers can build clear, explanatory narratives from multiple samples.

What questions can thematic analysis use?

Thematic researchers typically ask a string of open, topical, yet focused questions that invite elaboration from the respondent. They may often start with phrases such as:

- What do you think…?

- What is your opinion…?

- What are your ideas…?

- What do you remember…?

- Why do you believe…?

- What should we do about…?

Questionable themes that fit systematic thematic analysis may be vast and diverse (e.g. cosmology) or ‘small’ and unique (e.g. specific event memories). Questions can be segued into additional, clarifying questions (if relevant).

Approaches to thematic analysis

Like most methodologies, the 6-step analysis contains polarized sub-approaches. These determine how the questioning proceeds and how the gathered qualitative data is processed. A single thematic study may also use a ‘hybrid’ approach.

Inductive vs. deductive thematic analysis

| Inductive Analysis | Deductive Analysis |

| • Lets the data gathered from participants determine the study's themes. • It's useful for studying specific events, fleeting trends, and sub-cultures. • It can also open up complicated topics about which little is currently known. |

• Detects. • Like an investigator with only a vague clue, deductions build on existing knowledge (e.g. past papers) to help set the broad avenues of enquiry. • They're useful for expanding on an already vast body of knowledge or specific topical insights. |

Semantic vs. latent thematic analysis

| Semantic Analysis | Latent Analysis |

| • Looks solely at the surface-level prose in the text, i.e., a semantic analyst may assume that participants generally say what they nasty and nasty what they say. • This type of analysis records explicit content without further speculation, lending objectivity to results. • However, it may easily miss highlighting themes that are not straightforward (e.g. implicit opinions). |

• Assumes that people might often suggest more in speech than they're directly saying. • It examines the subtext of transcripts. • Furthermore, it focuses more on decryption. • A latent study might detail how statements might contain hidden meanings and tangents that aren't immediately obvious to a casual reader. • It's great for pulling out euphemized or suppressed narrative threads and establishing deeper context. |

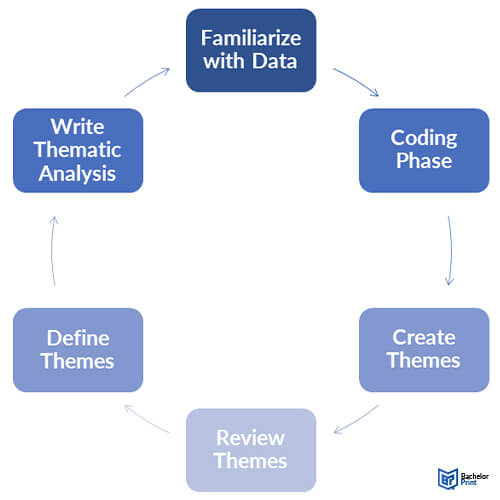

Step 1 of thematic analysis: Familiarization

After the interview phase, our researchers will collate and quickly review their initial findings. The prose within written transcripts is checked back for familiarity and errors. Researchers also transcribe any audio recordings into analyzable text.

Step 2 of thematic analysis: Coding

The coding phase sets out the common themes within the study and labels them via highlighted color coding.

Labeling common, linked statements codifies the subjects in play by dividing them into recurring themes. Any anomalies (i.e. unusual reactions) can also be flagged up for study.

Step 3 of thematic analysis: Constructing themes

Labeled codes are combined into broader, ‘umbrella’ themes that cover a wide range of recurring statements and opinions.

These themes generally identify recurring threads of thought that run through responses to the same question. As the study develops onward, several areas might be merged into a meta-category that better identifies and explains what’s happening.

Step 4 of thematic analysis: Reviewing themes

As the study finalizes, researchers take a short introspective look at exactly how they’re categorizing what they have found.

On reflection, some labels might fit into different themes better than their first assigned category. Others might reflect a strand of thought that initially seemed relevant but lacked significant presence elsewhere. Smaller themes might require careful reflection on whether they justify an entire category.

The researchers also watch carefully for observer bias.

Step 5 of thematic analysis: Defining themes

The penultimate step is reviewing category and theme names for clarity and accuracy.

Consistency, relevancy, and explanatory power are all given a second glance, as is each label’s succinctness. Titles are then changed, clarified, deleted, and merged as appropriate.

Step 6 of thematic analysis: Writing a thematic analysis

Once all the data’s been processed, categorized, and analysed, it’s time to create the study’s final paper.

The written summary serves as an explanation of how the data was collected, the methodology used to divide it, and outlines what conclusions and arguments (if any) can be drawn from what was found. It may also detail theories and potential topics for future study.

Every final thematic analysis should always contain:

- An introduction, stating aims and prior knowledge

- A methodology outline, stating how and where data was gathered

- A results section, outlining findings, labels, and categories identified

- A conclusion, detailing what can be drawn from the above

FAQs

Familiarization, coding, generating themes, Reviewing themes, defining themes, summarization (writing up).

Transcribed text from samples is browsed line-by-line for recurring patterns of thought, exposition, and opinion and marked.

Researchers often use coloured boxes or highlighter pens to divide scripts.

Yes. If your study exclusively gathers lots of repetitive, quantitative, numerical data, you might be better off using statistical analysis.